The first workshops appeared almost simultaneously with the cities themselves: in Italy - already in the 10th century. in France, England, Germany - from the 11th - early 12th centuries. Among the early workshops, for example, the Parisian workshop of candle makers, which arose in 1061, is known.

Most of all in the Middle Ages there were workshops involved in the production of food products: workshops of bakers, millers, brewers, butchers.

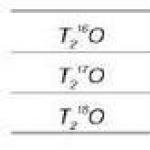

Many workshops were engaged in the production of clothing and shoes: workshops of tailors, furriers, shoemakers. Workshops associated with the processing of metals and wood also played an important role: workshops of blacksmiths, joiners, and carpenters. It is known that not only artisans united in unions; There were guilds of city doctors, notaries, jugglers, teachers, gardeners, and gravediggers.

A guild is a union of artisans of the same or related specialties in a medieval European city. Medieval cities were born and grew as centers of crafts and trade.

For a long time, there were few buyers of handicraft products. Attracting a buyer or customer was considered a great success.

Because of this, urban and rural craftsmen competed. The Union of Craftsmen could not only drive strangers away from the city market, it guaranteed high quality products - the main trump card in the fight against rivals. Common interests pushed the craftsmen to create unions called “guilds.”

Full members of the guilds were only masters who worked in their own workshops together with apprentices and apprentices who helped them. The main governing body of the workshop was the general meeting of craftsmen. It adopted the shop's charter and elected foremen, who monitored compliance with shop rules.

It is the shop regulations that allow us to learn a lot about the structure and life of the shops. The shop rules were particularly strict. They were aimed at maintaining the highest quality of products.

Another important concern of the guilds was maintaining the equality of their members. In order to prevent some craftsmen from enriching themselves at the expense of others, the workshop rules established the same conditions for all craftsmen in the production and sale of products. Each workshop established for its members the size of the workshop, the number of devices and machines placed in it, and the number of working apprentices and apprentices.

The guild regulations determined the volume of material that the master had the right to purchase for his workshop (for example, how many pieces of fabric a tailor could purchase). In some workshops, the production of which required expensive or rare imported materials, raw materials were purchased collectively and distributed equally among members of the union. Masters were forbidden to entice each other's apprentices and entice customers.

The content of the article

GUILDS AND WORKSHOPS(German Gilde, Middle Upper Zeche - association), in a broad sense - various types of corporations and associations (merchant, professional, public, religious), created to protect the interests of their members. Guilds existed already in the early period of history Mesopotamia And Egypt. In China, guilds long dominated economic life. Corporations of merchants and artisans engaged in one type of activity were widespread in Ancient Greece, as well as in the Hellenistic empires that existed in southwest Asia and Egypt. In the era Roman Empire associations known as collegia spread throughout the Mediterranean. Guilds covered all crafts, the most powerful uniting shipbuilders and ferrymen in coastal cities. In the era of the late Roman Empire, guilds became the object of state regulation. Membership became compulsory, since the law required sons to continue the work of their fathers. In ancient times, all guilds pursued both social and economic goals. They functioned as relief agencies and funeral societies. There were special initiation ceremonies and other rituals of a religious nature.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the system of collegia, under state supervision, was maintained in Byzantine Empire. It has been suggested (however, very controversial) that some Roman collegia continued to exist in a number of Italian cities throughout the Middle Ages. The question of the origin of merchant guilds, which appeared in the 11th century, as well as craft guilds dating back to a later time, still remains the subject of scientific debate. Various historians have seen their roots either in the Roman collegia, or in such early German institutions as law enforcement “deanery guilds” or drinking communities, or in the “economic microcosm of the manor” or in the charitable societies that arose in parishes.

Social and religious functions.

Social and religious motives played a large role in the activities of merchant guilds and craft guilds, although economic interests always remained in the foreground. Even where a guild did not grow out of a religious brotherhood, in the course of time it assumed such functions, or its members formed an associated society or brotherhood for this purpose. From the contributions of the guild members, a general fund was created, the proceeds from which were used to help the sick and needy, widows and orphans, as well as to arrange a decent burial for the members. Often, magnificent and elaborate religious ceremonies were organized in honor of the patron saint of this craft. The brothers were taught to live in love and mutual assistance, and the good name of the association was supported by strict rules and penalties for violators. The guilds played an important role in citywide festivities; their members took part in processions through the streets in traditional costumes intended for special occasions. Many guilds were responsible for the production mysteries(for example, on the feast of Corpus Christi), in which biblical stories or scenes from human history were reproduced - from creation to the Last Judgment.

Merchant guilds.

In Northern Europe, merchant guilds formed half a century earlier than craft guilds. They owe their origin to the revival of trade and the growth of cities in the 11th century. For the purpose of self-defense and in general commercial interests, merchants united in caravans along trade routes. Unions of this kind, initially created for a while, gradually acquired the character of permanent ones - either in the cities where the caravans were heading, or upon returning to their hometown. By the 12th century merchant guilds virtually completely monopolized trade in cities, which is primarily characteristic of Italy, France and Flanders.

Guild members and city authorities.

At first, membership in the merchant guilds was voluntary, but over time independent merchants were unable to compete with the guilds, and the resulting monopoly was accepted by feudal nobles and kings, as well as other cities. Since the guild now included all the wealthy merchants, it was able to exert significant influence on city government. The merchant guild was primarily a commercial organization that had quasi-legal rights over its members, as well as distinctive social and religious functions.

Unions of merchant guilds.

Sometimes, in order to establish control over their common foreign market, merchant guilds united into broad unions, which in Northern Europe received the name “Hansa” (from German Hanse - union, partnership). This type of association included the League of Flanders Towns, which was mainly engaged in the purchase of wool in England. The famous Hanseatic League (or Hansa), which united North German cities in the 14th–16th centuries, gained even greater influence. He controlled all trade in the Baltic and North Seas and had monopoly privileges in other places. The powerful Italian merchant guilds (in particular the Venetian ones) engaged in foreign trade operations were reminiscent of the trading companies that arose later in England and Northern Europe. Cargo transportation was strictly regulated by the state, and members of the guild were directly involved in trade.

Leaving aside the large cities involved in the extensive foreign trade in grain, wool and other goods, where capitalist relations began early, most cities in Northern Europe were small in size and oriented only to the domestic market. Residents of surrounding villages and hamlets brought agricultural products and raw materials to the city for sale, paid a fee for a place in the market, and with the proceeds they purchased city-produced products. Local authorities allowed merchants from other cities to sell in bulk only what the city needed, as well as to buy and export surplus city products. For this, merchants were obliged to pay duties if they did not have the corresponding benefits issued to them by their hometowns.

Trading rules.

It was important to eliminate competition between its own members and not allow more capable and energetic merchants to force weaker traders out of the market. Therefore, very strict measures were taken against price reduction and all kinds of unfair methods of competition, such as buying or holding goods, monopolizing goods, resale at higher prices, etc. However, despite fines and other punishments, including imprisonment, guilds were never able to eradicate these are prohibited methods of getting rich. A rule was then introduced that everyone who belonged to the guild must receive a share of any deal made by a guild member. In some cities, this applied only to those guild members who were in the city at the time the transaction was concluded. By regulating prices and ensuring that all members had roughly equal opportunities, the guilds prevented the emergence of a middleman class.

Craft shops.

At first, artisans were allowed into merchant guilds, although they were located below merchants in the social hierarchy. The guilds of small towns fully satisfied the interests of both, especially since there were no clear boundaries between the merchant and the artisan. But in large cities, the development of trade and industry led to an increase in the number of workers and to the specialization of artisans, who began to unite by craft and create their own merchant-type corporations, called guilds. The process of creating workshops was facilitated by the fact that people engaged in one type of activity tended to settle in one city block or on one street, where they kept workshops and immediately sold their products.

Origin of workshops.

The origins of the guilds can be found in the religious brotherhoods that arose in Northern Europe from the end of the 11th century. Such brotherhoods were formed from parishioners of one church to perform funeral rites and celebrate the day of the local patron saint. It is quite natural that during meetings, members of the brotherhood also discussed issues of a commercial nature, and from here an association could easily arise, the main function of which was to supervise the production of products in this industry.

Specialization and rights.

Merchant guilds, which, as a rule, stood at the head of city government, were usually interested in the self-government of the guilds. At the same time, the merchants sought to maintain their power over the artisans. However, over time, the workshops acquired independence. A king or another ruler could grant one or another workshop monopoly privileges. Almost all workshops enjoyed such privileges. By the 13th century. they developed in all cities of Northern Europe and England, reaching the peak of their development over the next two centuries. As production became more specialized, new ones were spun off from old workshops. For example, in the textile industry, workshops of carders, fullers, dyers, spinners and weavers arose.

Relations with city authorities.

In some countries, especially Germany, municipal authorities retained the right to regulate the activities of workshops and appoint their managers. In other countries, primarily in France and the Netherlands, where cities began to develop earlier and reached greater maturity, the guilds sought complete independence in every possible way; they even tried to join merchant guilds in order to control city government. In many cities such rights were granted to them, and some cities, such as Liege and Ghent, found themselves entirely at the mercy of the guilds. However, the fierce rivalry of the guilds led to anarchy, which lasted in Ghent until 1540, and ended in Liege a century and a half later (in 1684), when, through the efforts of the local bishop, the guilds were deprived of all political influence.

Workshop tasks.

The purpose of the workshops was to ensure a monopoly in the production and marketing of products. But a monopoly was possible only as long as the products were intended for the local market, and everything was much more complicated when it came to other cities or artisans of a given city who were not members of the workshop. In the interests of their own members and consumers, the workshops needed to exercise control over prices, wages, working conditions and product quality. To this end, workshops prohibited night work, since poor lighting and lack of proper supervision could lead to careless or dishonest work, and also because after-hours work gave an advantage to some workshops over others. Guild workers were required to work in rooms facing the street, in full view of everyone; work on Sundays and holidays was prohibited.

Regulation.

The production process, from the primary processing of raw materials to the final product, was strictly regulated: all details were specified, standards were set for everything, and the volume of production was limited. In order to maintain equality and uniformity, innovations of any kind were prohibited (except those that would benefit all members) - whether they concerned tools, raw materials or technology. Everyone had the opportunity to rise to a certain level of well-being, but not higher than that. This attitude corresponded to the medieval concept of social order, according to which everyone had to be satisfied with their position in the social hierarchy. This attitude was also supported by the concept of a “fair price” and religious dogmas. Enormous efforts were made to keep this established rigid economic structure intact. Anyone who violated the rules faced severe punishment - a fine, imprisonment, and even a ban on practicing the craft. The sheer abundance of various kinds of rules and restrictions testifies to the cunning techniques some artisans resorted to in order to go beyond the regulations.

Composition of workshops.

The guilds included masters who owned workshops and shops, journeymen (hired workers) and apprentices. In the affairs of the guild, apprentices had limited voting rights; apprentices had no voting rights at all. During the heyday of the guilds, masters attached great importance to the education of their shifts, so a capable and hardworking student could count on eventually becoming a master.

Education.

Anyone could become an apprentice to master a certain craft. But according to established rules, only those who had passed the apprenticeship stage were accepted into the workshop. Even the son of a master, who had the right to inherit his father's business, was obliged to go through the apprenticeship stage, learning the craft from his father or another master. Later, the master’s son began to take advantage of joining the workshop. The apprentice lived and worked with the master under the terms of a contract signed by the boy's parents or guardians. Usually the student was obliged to be hardworking and devoted, to obey the master unquestioningly, to keep his goods and the secrets of the craft, and to respect his interests in everything. He also promised not to marry until he completed his studies, not to become a regular at taverns and other entertainment establishments, and not to commit unseemly acts that could tarnish the master’s reputation. For his part, the master obliged to teach the boy a craft, providing him with food, housing, clothing and pocket money, and also to guide his morality, resorting to punishment if necessary. Sometimes the student's parents paid the master for these services. If it happened that a teenager went on the run, he was returned to the workshop and severely punished. On the other hand, the master himself was subject to punishment for abuse of power or neglect of his duties.

Requirements for the student.

Both the guilds and the city authorities were interested in ensuring that students, who were often characterized by riotousness and other vices, would eventually become masters and respectable citizens, and therefore jointly established rules for admitting students. Attention was paid to factors of various kinds - moral character, age, length of study, number of students per master, etc. Typically, students became students between the ages of 14 and 19, and the duration of training varied greatly from place to place and from era to era. In England and some other countries, a young man was usually apprenticed for 7 years. Later, workshops began to deliberately delay training periods in order to limit the number of applicants for the position of a master. For the same reasons, masters were forbidden to keep more than a certain number of students at a time. This was also done so that, due to the cheap labor of teenagers, some masters would not gain an advantage over others.

Acceptance of candidates.

A worthy candidate did not encounter any special obstacles when joining the workshop. This was considered a craftsman aged 23–24, who had completed a full course of training and was ready to open his own workshop and make contributions to the workshop treasury. Later, the applicant was required to create something outstanding (the so-called “masterpiece”, French “work of a master”). If the applicant was trained in another city, he had to find guarantors in the workshop where he was going to join. An apprentice who married the daughter of his mentor often became a full partner of his father-in-law, and sometimes with his help he started his own business. Without such advantages, the apprentice, in order to accumulate the capital necessary to set up his own workshop, had to work for hire, wandering around cities and villages in search of better earnings. As production developed, more and more initial capital was required, and the journeyman stage became inevitable and, over time, mandatory. In England, to become a master, it was necessary to work as an apprentice for 2–3 years.

Journeymen.

From the 14th century workshops began to avoid an overabundance of competing craftsmen in a limited market. And since the apprentices were not able to save any significant amount from their meager wages, many of them never reached the rank of masters. At the same time, the most enterprising masters began to do without the long-term cultivation of students, preferring to hire apprentices who were entrusted with special operations that did not require extensive training. As a result, a class of permanent wage workers arose and, at the same time, a hereditary industrial aristocracy based on the ownership of property resulting from the investment of significant capital in production. The latter shows many similarities with the hereditary aristocracy that had already emerged among the ancient merchant guilds. This layer of artisan-capitalists first asserted itself in the export industries, and then, as trade developed, stood out in all areas of production.

Journeymen's unions.

The exclusion of apprentices from the number of full members and their loss of any influence on the affairs of the guilds led to the fact that from the 14th century. they began to create their own independent associations. This process took place especially actively in continental Europe, where associations of apprentices acquired even greater importance than the “yeoman unions” in England. The forms of worker organization varied, but all of these associations fought for increased wages and limited exploitation, all opposed to the developing capitalist economy. Many unions developed a sophisticated system of secret rituals, similar to those practiced by free masons, which sometimes brought persecution from the church on them. The apprentices' unions resorted to various forms of struggle - they organized strikes, street riots and lockouts. In particular, they protested against the hiring of foreigners and untrained workers. In response, the masters, using their influence on the city authorities, officially banned unions of apprentices and unleashed persecution. This was the case in many cities in Flanders and Italy. The authorities tried to prevent full-time apprentices from taking outside jobs, opening their own workshops, and keeping apprentices. Friction arose especially often in those industries where many hired workers were employed. At some stage, the workers could prevail, but more often the forces opposing them - the union of employers, members of the workshops and city authorities, who had political and economic power - won.

The decline of the guild system.

During the late Middle Ages, the guilds became increasingly closed, membership in some became hereditary, and they tenaciously held on to their privileges, although the growth of capitalist production in other cities had already reduced their importance. They remained viable only on the scale of the local market, and only where they enjoyed the support of the authorities.

Development of capitalist production.

By the beginning of the 16th century. the workshop system no longer met the needs of capitalist production, oriented towards a wide market. Those workshops that produced products for export from imported raw materials were in an advantageous position. They took control of local small producers. For example, in textile production in Florence and Flanders, capitalists supplied wool or yarn to artisans and then bought the fabrics produced from them. Small producers, who did not have access to sources of raw materials and markets, were effectively reduced to the position of hired workers working for wealthy merchants.

The struggle of the workshops.

In the second half of the 14th century. A wave of urban revolutions swept across many areas of Europe. In Florence, the lower guilds of manufacturers, who at that moment were supported by masses of unorganized workers, rebelled against the merchant guilds that held power in the city. In some cases, these uprisings brought to power tyrants (in the ancient sense of the word), who took on the role of champions of the people's cause, such as the Florentine Medici. In the Flemish cities, the citizen uprisings of 1323–1328 brought to power the Counts of Flanders and eventually the French king.

Transition to home work.

The system of restrictions and ongoing conflicts with producers forced capitalists to look for new ways to free themselves from this dependence. At the end of the 15th century. Flemish textile traders stopped buying yarn and fabric in cities that were constantly shaken by unrest and turned their attention to small towns and villages, where they had not heard of workshops and costs were lower. Having received raw materials and a self-spinning wheel, the peasants and their families worked at home, their work was paid by the piece. The home-based system was quite suitable for the textile production already familiar to peasants, which was not as difficult to master as other crafts. Soon, the system of home work began to be applied to other branches of production, as a result of which many ancient industrial cities began to lose their importance, so that only the majestic buildings of the guild meetings now reminded of their former greatness.

The disappearance of guilds and workshops.

In one form or another, guilds existed until the 19th century. Even the richest merchants engaged in the export trade saw benefit in their preservation. At the end of the 15th century. English textile exporters had to unite to gain a foothold on the continent, where they encountered strong opposition from the Hanseatic League. But over time, the guild system became unnecessary. The guilds continued to exist for several centuries, although they constantly lost their economic importance. For some time they tried to maintain a monopoly in the cities, but their claims to exclusivity conflicted with the new economic conditions. In France, the guilds were disbanded in 1791, during Great French Revolution. In Prussia and other German states they gradually disappeared during the first half of the 19th century; in England, the remnants of the workshops were liquidated by acts of 1814 and 1835.

Literature:

Gratsiansky N.P. Parisian craft shops at 13–14 centuries. Kazan, 1911

Rutenburg V.I. Essay on the history of early capitalism in Italy. M. – L., 1951

Stoklitskaya-Tereshkovich V.V. The problem of the diversity of the medieval guild in the West and in Rus'. – In the book: Middle Ages, vol. 3. M., 1951

Polyansky F.Ya. Essays on the socio-economic policy of workshops in Western European cities 13–15th century. M., 1952

Levitsky Y.A. Cities and urban crafts in England at 10–12th century. M. – L., 1960

The production basis of the medieval city was crafts and “manual” trades. A craftsman, like a peasant, was a small producer who owned the tools of production and independently ran his own farm, based primarily on personal labor.

“An existence appropriate to his position, and not exchange value as such, not enrichment as such...”1 was the goal of the artisan’s work. But unlike the peasant, the expert craftsman, firstly, from the very beginning was a commodity producer and ran a commodity economy. Secondly, he did not need land as a means of direct production. Therefore, urban crafts developed and improved incomparably faster than agriculture and rural, home crafts. It is also noteworthy that in the urban craft, non-economic coercion in the form of personal dependence of the worker was not necessary and quickly disappeared. Here, however, there were other types of non-economic coercion related to the guild organization of crafts and the corporate-class, essentially feudal nature of the urban system (coercion and regulation by the guilds and the city, etc.). This coercion came from the townspeople themselves.

A characteristic feature of crafts and other activities in many medieval cities of Western Europe was a corporate organization: the unification of persons of certain professions within each city into special unions - guilds, brotherhoods. Craft guilds appeared almost simultaneously with the cities themselves: in Italy - already in the 10th century, in France, England, Germany - from the 11th - early 12th centuries, although the final registration of the guilds (receiving special letters from kings and other lords, drawing up and recording shop regulations) occurred, as a rule, later.

1 Archive of Marx and Engels. T. II (VII), p. 111.

The guilds arose because urban artisans, as independent, fragmented, small commodity producers, needed a certain unification to protect their production and income from feudal lords, from the competition of “outsiders” - unorganized artisans or immigrants from the village constantly arriving in the cities, from artisans of other cities, and and from neighbors - craftsmen. Such competition was dangerous in the conditions of the then very narrow market and insignificant demand. Therefore, the main function of the workshops was to establish a monopoly on this type of craft. In Germany it was called Zynftzwang - guild coercion. In most cities, belonging to a guild was a prerequisite for practicing a craft. Another main function of the guilds was to establish control over the production and sale of handicrafts. The emergence of guilds was determined by the level of productive forces achieved at that time and the entire feudal-class structure of society. The initial model for the organization of urban crafts was partly the structure of the rural community-marks and estate workshops-magisteriums.

Each of the guild foremen was a direct worker and at the same time the owner of the means of production. He worked in his workshop, with his tools and raw materials and, in the words of K. Marx, “fused with his means of production as closely as a snail with a shell”1. As a rule, the craft was passed down through generations: after all, many generations of artisans worked using the same tools and techniques as their great-grandfathers. New specialties that emerged were organized into separate workshops. In many cities, dozens, and in the largest - even hundreds of workshops gradually appeared. A guild artisan was usually assisted in his work by his family, one or two apprentices and several apprentices. But only the master, the owner of the workshop, was a member of the workshop. And one of the important functions of the workshop was to regulate the relations of masters with apprentices and apprentices.

The master, journeyman and apprentice stood at different levels of the guild hierarchy. Preliminary completion of the two lower levels was mandatory for anyone who wished to become a member of the guild. Initially, each student could eventually become a journeyman, and the journeyman could become a master.

The members of the workshop were interested in ensuring that their products received unhindered sales. Therefore, the workshop, through specially elected officials, strictly regulated production: it made sure that each master produced products of a certain type and quality. The workshop prescribed, for example, what width and color the fabric produced should be, how many threads should be in the warp, what tools and raw materials should be used, etc. Regulation of production also served other purposes: so that the production of members of the workshop remained small-scale, that

1 Marx K., Engels F. Soch. 2nd ed. T. 23. P. 371.

none of them would push another master out of the market by producing more products or making them cheaper. To this end, guild regulations rationed the number of journeymen and apprentices that a master could keep, prohibited work at night and on holidays, limited the number of machines and raw materials in each workshop, regulated prices for handicraft products, etc.

The guild organization of crafts in cities was one of the manifestations of their feudal nature: “... the feudal structure of land ownership in cities corresponded to corporate ownership, the feudal organization of crafts”1. Until a certain time, such an organization created the most favorable conditions for the development of productive forces and urban commodity production. Within the framework of the guild system, it was possible to further deepen the social division of labor in the form of establishing new craft workshops, expanding the range and improving the quality of goods produced, and improving craft skills. Within the framework of the guild system, the self-awareness and self-esteem of urban craftsmen increased.

Therefore, until approximately the end of the 14th century. workshops in Western Europe played a progressive role. They protected artisans from excessive exploitation by feudal lords; in the conditions of the narrow market of that time, they ensured the existence of urban small producers, softening competition between them and protecting them from the competition of various outsiders.

The guild organization was not limited to the implementation of basic socio-economic functions, but covered all aspects of the life of a craftsman. The guilds united the townspeople to fight the feudal lords, and then the domination of the patriciate. The workshop participated in the protection of the city and acted as a separate combat unit. Each workshop had its own patron saint, sometimes also its own church or chapel, being a kind of church community. The workshop was also a mutual aid organization, providing support to needy craftsmen and their families in the event of illness or death of the breadwinner.

It is obvious that the guilds and other city corporations, their privileges, and the entire regime of their regulation were public organizations characteristic of the Middle Ages. They corresponded to the productive forces of that time, and were similar in character to other feudal communities.

The guild system in Europe, however, was not universal. It has not become widespread in a number of countries and has not reached its completed form everywhere. Along with it, in many cities of Northern Europe, in the south of France, in some other countries and regions, there was a so-called free craft.

But even there there was regulation of production, protection of the monopoly of urban artisans, only these functions were carried out by city government bodies.

1 Marx K., Engels F. Soch. 2nd ed. T. 3. P. 23. A unique corporate property was the monopoly of a workshop in a certain specialty.

Craft guilds played an important role in the development of commodity production in Europe in the process of forming a new social group - the class of hired workers. The essay is of interest to correspondence students when writing a test in history.

Download:

Preview:

STATE BUDGET PROFESSIONAL

EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF KRASNODAR REGION

"ANAPSKY AGRICULTURAL TECHNIQUE"

MEDIEVAL CRAFT SHOP (XIII-XV CENTURIES)

Completed by: teacher of socio-economic disciplines

Eisner Tatyana Viktorovna

Anapa, 2016

Medieval craft workshops (XIII-XV centuries)

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………… | |

1. Reasons for the emergence of workshops and their functions………………………... | |

2. Shop regulation. Master, student, journeyman..…………….. | |

3. Decomposition of the guild system……………………………………………. | |

Conclusion………………………………………………………………… | |

List of sources and literature………………………………………………………... |

Introduction.

Craft shops in Western Europe appeared almost simultaneously with cities: in Italy already in the 10th century, in France, England and Germany from the 11th and early 12th centuries. It is worth noting that the final formalization of the guild system with the help of charters and statutes occurred, as a rule, later.

The guilds played an important role in the development of commodity production in Europe, in the formation of a new social group - wage workers, from whom the proletariat was subsequently formed.

Therefore, the study of the problem of the emergence of guilds as an organization of crafts in medieval Europe is relevant.

The purpose of this work is to identify the main features of the guild organization of crafts in medieval Europe.

Tasks:

1) reveal the main reasons for the emergence of workshops, their functions, features of workshop regulation;

2) to identify the features of the relationship between masters, their students and apprentices in medieval guilds, between the guilds and the patriciate;

3) reveal the reasons for the decomposition of the guild organization of the medieval city.

1. Reasons for the emergence of workshops and their functions.

Medieval cities developed primarily as centers of concentration of handicraft production. Unlike peasants, artisans worked to meet market needs by producing products for sale. The production of goods was located in the workshop, on the ground floor of the artisan's premises. Everything was made by hand, using simple tools, by one master from start to finish. Usually the workshop served as a shop where the artisan sold the things he produced, thus being both the main worker and the owner.

The limited market for handicraft goods forced craftsmen to look for ways to survive. One of them was the division of the market and the elimination of competition. The well-being of the artisan depended on many circumstances. Being a small manufacturer, the artisan could produce only as much goods as his physical and intellectual abilities allowed. But any problems: illness, error, lack of necessary raw materials and other reasons could lead to the loss of the customer, and, therefore. and livelihood.

To solve pressing problems, artisans began to join forces. This is how guilds appear - closed organizations (corporations) of artisans of a particular specialty within one city, created with the aim of eliminating competition (protecting production and income) and mutual assistance. Let us present the reasons and goals of the emergence of guilds-unions of medieval artisans in the form of a table.

Table 1.

Reasons and purpose of the emergence of workshops.

Organization of life | Need for security | Internal economic | Foreign economic |

1.Organization of everyday life | 1.Organization of city defense in case of war. | 1. Protection from competition. | 1. Development of uniform rules in the production and sale of products |

2.Mutual assistance | 2. Protection from attacks by robber knights. | 2. division of the sales market in conditions of market narrowness. | 2. Creation of the same conditions for all masters. |

Members of the workshop helped each other learn new ways of crafting, but at the same time they guarded their secrets from other workshops. The elected leadership of the workshop carefully ensured that all members of the workshop were in approximately the same conditions, so that no one got rich at the expense of another or lured away customers. For this purpose, strict rules were introduced, which clearly indicated how many hours one could work, how many machines and assistants to use. Violators were expelled from the workshop, which meant loss of livelihood. There was also strict control over the quality of the goods. In addition to production, the workshops also organized the life of artisans. Members of the workshop built their own church, school, and celebrated holidays together. The workshop supported widows, orphans, and disabled people. In the event of a city siege, members of the workshop, under their own flag, formed a separate combat unit, which was supposed to defend a certain section of the wall or tower.

“One of the main functions of the workshops was the establishment of monopolies for this type of craft. In most cities, belonging to a guild was a prerequisite for practicing a craft. Another main function of the guilds was to establish control over the production and sale of handicrafts." 1 . Dozens of workshops gradually appeared in cities, and even hundreds of workshops in large cities.

An important role was played by the workshop charter - rules binding on all members of the workshop:

- Do things according to a single pattern;

- Have the permitted number of machines, students, journeymen;

- Do not lure away customers from each other;

- Do not work on holidays or by candlelight;

- Sell products at a prescribed price;

- Purchase raw materials from certain suppliers.

Foremans served to enforce the regulations and punish violators.

2. Shop regulation. Master, student, journeyman.

Members of each workshop were interested in ensuring unhindered sales of their products. Therefore, the workshop strictly regulated production and, through specially elected workshop officials, ensured that each master member of the workshop produced products of a certain type and quality.

The workshop prescribed, for example, what width and color the fabric should be, how many threads should be in the warp, what tool and material should be used, and so on.

The regulation of production also served other purposes: being an association of independent small commodity producers, the workshop zealously ensured that the production of all its members remained small in nature, so that none of them would displace other craftsmen from the market by producing more products. Therefore, guild regulations strictly limited the number of journeymen and apprentices that one master could have, prohibited work at night and on holidays, limited the number of machines on which an artisan could work, regulated stocks of raw materials, prices for handicraft products, and the like.

“Regulation of shop life was also necessary so that the members of the shop would maintain its high reputation not only by the quality of the products produced, but also by their good behavior.” 1 .

The members of the workshop were craftsmen. They elected the head of the workshop or the workshop council. The masters were assisted by apprentices. They were not considered members of the guilds, and, therefore, did not enjoy many of the advantages of craftsmen; they did not have the right to open their own business, even if they were fluent in their craft. To become a master, one had to pass a serious test. The candidate presented a product to the chief craftsmen of the workshop, which, of course, indicated that he had completely mastered all the tricks of his craft. This exemplary product was called a masterpiece in France. In addition to making a masterpiece, an apprentice who wanted to become a master had to spend a lot on treating the members of the workshop. From decade to decade, becoming a master became increasingly difficult for everyone except the sons of the masters themselves. The rest turned into “eternal apprentices” and could not even hope to someday join the workshop.

Dissatisfied apprentices sometimes conspired against the masters and even started rebellions. Even lower than the apprentices were the apprentices. As a rule, even in childhood they were sent to be trained by some master and paid him for training. At first, the master often used his students as household servants, and later, without much haste, he shared with them the secrets of his work. A grown-up student, if his studies benefited him, could become an apprentice. At first, the position of apprentices had strong features of “family” exploitation. The apprentice's status remained temporary; he himself ate and lived in the master's house, and marriage to the master's daughter could crown his career. And yet, “family” traits turned out to be secondary. The main thing that determined the social position of the apprentice and his relationship with the owner was wages. It was the hired side of the journeyman’s status, his existence as a hired worker, that had a future. The guild foremen increasingly exploited the apprentices. The duration of their working day was usually very long, 14-16, and sometimes 18 hours. The apprentices were judged by the guild court, that is, again, by the master. The workshops controlled the life of journeymen and students, their pastime, spending, and acquaintances. The Strasbourg "Regulation on Hired Workers" in 1465, putting apprentices and domestic servants on the same level, orders them to return home no later than 9 o'clock in the evening in winter and 10 o'clock in summer, prohibits visiting public houses, carrying weapons in the city, and dressing everyone in the same dress. and wear the same decals. The last ban was born out of fear of a conspiracy of apprentices.

3. Decomposition of the guild system.

In the 14th century, great changes took place within craft production. In the first period of their existence, the guilds played a progressive role. But the desire of the guilds to preserve and perpetuate small-scale production, traditional techniques and tools, hampered the further development of society. Technical advances contributed to the development of competition, and the workshops turned into a brake on industrial development, an obstacle to further growth of production.

However, no matter how much the guild regulations prevented the development of competition between individual artisans within the guild, as the productive forces grew and the domestic and foreign markets expanded, it grew more and more. Individual artisans expanded their production beyond the limits established by the guild regulations. Economic and social inequality in the workshop increased. Wealthy craftsmen, owners of larger workshops, began to practice handing over work to small craftsmen, supplying them with raw materials or semi-finished products and receiving finished products. “Thus, from among the previously unified mass of small artisans, a wealthy guild elite gradually emerged, exploiting the small craftsmen - the direct producers” 1 . The entire mass of students and journeymen also fell into the position of being exploited.

In the XIV-XV centuries, during the period of the beginning of the decline and disintegration of the guild craft, the situation of students and journeymen sharply worsened. If in the initial period of the existence of the guild system, a student, having completed an apprenticeship and becoming a journeyman, and then having worked for some time for a master and having accumulated a small amount of money, could count on becoming a master (the costs of setting up a workshop given the small-scale nature of production were small), now access to this was actually closed to students and apprentices. In an effort to defend their privileges in the face of growing competition, masters began to make it in every possible way difficult for journeymen and apprentices to obtain the title of master.

The so-called “shop closure” occurred. The title of master became practically available to journeymen and students only if they were close relatives of the masters. Others, in order to receive the title of master, had to pay a very large entrance fee to the workshop's cash desk, perform exemplary work requiring large financial expenditures - a masterpiece, arrange an expensive treat for the members of the workshop, and so on. Thus deprived of the opportunity to ever become masters and open their own workshop, apprentices turned into “eternal apprentices,” that is, in fact, into hired workers.

Peasants who lost their land, as well as students and journeymen, who actually turned into hired workers, were an integral part of that layer of the urban population that can be called the pre-proletariat and which also included non-guild, various kinds of unorganized workers, as well as impoverished members of the guild - small artisans, increasingly dependent on the large masters who had become rich and differed from apprentices only in that they worked at home. “While not being a working class in the modern sense of the word, the pre-proletariat was “a more or less developed predecessor of the modern proletariat.” He made up the bulk of the lower layer of townspeople - the plebeians." 1

As social contradictions within the medieval city developed and intensified, the exploited sections of the urban population began to openly oppose the city elite that was in power, which now included in many cities the richer part of the guild masters, the guild aristocracy. This struggle also included the lowest and most powerless layer of the urban population - the lumpen proletariat, that is. a layer of people deprived of certain occupations and permanent residence, standing outside the feudal class structure. During the period of the beginning of the decomposition of the guild system, the exploitation of the direct producer - the small artisan - by trading capital developed. Commercial, or merchant, capital is older than the capitalist mode of production. It represents the historically oldest free form of capital, existing long before capital subjugated production itself, and arising earliest of all in trade. Merchant capital operates in the sphere of circulation, and its function is to serve the exchange of goods in the conditions of commodity production in a slave society, and in a feudal and capitalist one. As commodity production developed under feudalism and guild crafts decomposed, commercial capital gradually began to penetrate into the sphere of production and began to directly exploit the small artisan. Usually, the merchant-capitalist initially acted as a buyer. He bought raw materials and resold them to the artisan, bought the goods of the artisan for further sale, and often put the less wealthy artisan in a position dependent on him. Especially often, the establishment of such economic dependence was associated with the supply of raw materials, and sometimes tools, to the artisan on credit. Such a craftsman who fell into bondage to a buyer or even a downright bankrupt artisan had no choice but to continue working for the merchant-capitalist, only no longer as an independent commodity producer, but as a person deprived of the means of production, that is, in fact, a hired worker. “This process served as the starting point for the capitalist manufacture that emerged during the period of disintegration of medieval craft production. All these processes took place especially vividly, although in a peculiar way, in Italy.” 1 .

Conclusion.

Having considered the problems of organizing crafts in a medieval city, we can draw the following conclusions.

The emergence of guilds was determined by the level of productive forces achieved at that time and the entire feudal-class structure of society. The main reasons for the formation of guilds were the following: urban artisans, as independent, fragmented, small commodity producers, needed a certain unification to protect their production and income from feudal lords, from the competition of “outsiders” - unorganized artisans or immigrants from the village constantly arriving in cities, from artisans of other cities , and from neighbors - masters. The entire life of a medieval guild artisan - social, economic, industrial, religious, everyday, festive - took place within the framework of the guild brotherhood. The members of the workshop were interested in ensuring that their products received unhindered sales. Therefore, the workshop, through specially elected officials, strictly regulated production. “Regulation of shop life was also necessary so that the members of the shop would maintain its high reputation not only by the quality of the products produced, but also by their good behavior.” 1 .

As the productive forces grew and the domestic and foreign markets expanded, competition between artisans within the workshop inevitably increased. Individual artisans, contrary to guild regulations, expanded their production, property and social inequality developed between masters, and the struggle between masters and “eternal apprentices” intensified.

From the end of the 14th century. The guild organization of crafts, aimed at preserving small-scale production, was already beginning to restrain technical progress and the spread of new tools and production methods. The workshop charter did not allow the consolidation of workshops, the introduction of an operational division of labor, in fact prohibited the rationalization of production, and restrained the development of individual skills and the introduction of more advanced technologies and tools.

Guilds played an important role in the development of commodity production in medieval Europe, influencing the formation of social relations in the modern era.

List of sources and literature:

Sources

1. Augsburg Chronicle // Medieval city law of the 12th – 13th centuries. /Ed. S. M. Stama. Saratov, 1989. pp. 125 – 126.

2. Contracts for hiring a student // Medieval city law of the 12th – 13th centuries. /Ed. S. M. Stama. Saratov, 1989. pp. 115 – 116.

3. Book of customs // History of the Middle Ages. Reader. In 2 parts. Part 1 M., 1988.P. 178 – 180.

4. Message from the Constance City Council // History of the Middle Ages. Reader. In 2 parts. Part 1 M., 1988.P. 167 – 168.

5. A call for a strike addressed by the apprentice furriers of Vilshtet to the apprentice furriers of Strasbourg // History of the Middle Ages. Reader. In 2 parts. Part 1 M., 1988.P. 165.

6. Guild charter of silk weavers // Medieval city law of the 12th – 13th centuries. /Ed. S. M. Stama. Saratov, 1989. pp. 113-114.

Literature

7. City in the medieval civilization of Western Europe / Ed. A.A. Svanidze M., 1999 -2000.T. 1-4.

8. Gratsiansky N.P. Parisian craft workshops in the XIII - XIV centuries. Kazan, 1911.

9. Svanidze A. A. Genesis of the feudal city in early medieval Europe: problems and typology//City life in medieval Europe. M., 1987.

10. Stam S. M. Economic and social development of the early city. (Toulouse X1 - XIII centuries) Saratov, 1969.

11. Stoklitskaya-Tereshkovich V.V. The main problems of the history of the medieval city of the X - XV centuries. M., 1960.

12. Kharitonovich D. E. Craft. Guilds and myths // City in the medieval civilization of Western Europe. M.1999. P.118 – 124.

13. Yastrebitskaya A. L. Western European city in the Middle Ages // Questions of history, 1978, No. 4. pp. 96-113.

1 Stam S. M. Economic and social development of the early city. (Toulouse X1 - XIII centuries) Saratov, 1969.